|  | |

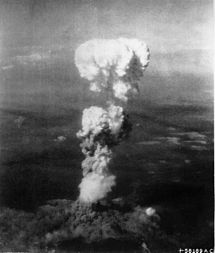

| The Fat Man mushroom cloud resulting from the nuclear explosion over Nagasaki rises 18 km (11 mi, 60,000 ft) into the air from the hypocenter |

Voice and Silence in the First Nuclear War: Wilfred Burchett and Hiroshima

By Richard Tanter*

Hiroshima had a profound effect upon me. Still does. My first reaction was personal relief that the bomb had ended the war. Frankly, I never thought I would live to see that end, the casualty rate among war correspondents in that area being what it was. My anger with the US was not at first, that they had used that weapon – although that anger came later. Once I got to Hiroshima, my feeling was that for the first time a weapon of mass destruction of civilians had been used. Was it justified? Could anything justify the extermination of civilians on such a scale? But the real anger was generated when the US military tried to cover up the effects of atomic radiation on civilians – and tried to shut me up. My emotional and intellectual response to Hiroshima was that the question of the social responsibility of a journalist was posed with greater urgency than ever.

Wilfred Burchett 1980 [1]

Wilfred Burchett entered Hiroshima alone in the early hours of 3 September 1945, less than a month after the first nuclear war began with the bombing of the city. Burchett was the first Western journalist – and almost certainly the first Westerner other than prisoners of war – to reach Hiroshima after the bomb. The story which he typed out on his battered Baby Hermes typewriter, sitting among the ruins, remains one of the most important Western eyewitness accounts, and the first attempt to come to terms with the full human and moral consequences of the United States’ initiation of nuclear war.

For Burchett, that experience was a turning point, ‘a watershed in my life, decisively influencing my whole professional career and world outlook’. Subsequently Burchett came to understand that his honest and accurate account of the radiological effects of nuclear weapons not only initiated an animus against him from the highest quarters of the US government, but also marked the beginning of the nuclear victor’s determination rigidly to control and censor the picture of Hiroshima and Nagasaki presented to the world.

The story of Burchett and Hiroshima ended only with his last book, Shadows of Hiroshima, completed shortly before his death in 1983. In that book, Burchett not only went back to the history of his own despatch, but more importantly showed the broad dimensions of the ‘coolly planned’ and manufactured cover-up which continued for decades. With his last book, completed in his final years in the context of President Reagan’s ‘Star Wars’ speech of March 1983, Burchett felt ‘it has become urgent – virtually a matter of life or death – for people to understand what really did happen in Hiroshima nearly forty years ago . . . It is my clear duty, based on my own special experiences, to add this contribution to our collective knowledge and consciousness. With apologies that it has been so long delayed . . .” [2]

That one day in Hiroshima in September 1945 affected Burchett as a person, as a writer, and as a participant in politics for the next forty years. But Burchett’s story of that day, and his subsequent writing about Hiroshima, have a greater significance still, by giving a clue to the deliberate suppression of the truth about Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and to the deeper, missing parts of our cultural comprehension of that holocaust.

[Read Burchett's eye-witness testimony below]

One Day in Hiroshima: 3 September 1945